Point perspective is one of the first things you are taught about in art and is fundamental to the history of Western art. It is a device that convinces the eye a flat surface has depth.

To draw the eye in, we close the picture in. We take the eye through the foreground, the middle ground and the background. This gives us a sense of scale, space and perspective that we understand instinctively. Offering this sense of perspective to the viewer is key to understanding many drawings and paintings and it is fundamental to architectural reasoning.

What is point perspective?

Stand in the middle of a regular street filled with buildings and notice how the perspective triangulates into the distance. The two ends of the road become closer together the further they are from where you stand. Eventually, with enough perspective, joining together in the farthest distance. This is all about scale and how the human eye perceives it.

Notable use of point perspective

Perspective in drawings and paintings became widely used in the Renaissance, when great painters like da Vinci and Raphael created huge frescoes taking in people among buildings and large spaces. These complicated images needed to make use of the whole surface, including the different depths of fore, middle and background.

What are the different types of point perspective?

Linear perspective

The most common form of perspective is probably a linear perspective. This is the simple act of creating the illusion of depth on a flat surface. All parallel lines converge into a single vanishing point on the composition’s horizon line. This means you can draw lines from corner to corner, side to side and the point at which they will cross will usually be the point of perspective.

Master of linear perspective: Raphael

Renaissance painters mastered the art of perspective. As Leonardo da Vinci unmasked the mysteries of proportion of the human body with The Vitruvian Man, he and his contemporaries also created lines of focus. It was at this point that artists began to fill in the backgrounds more.

One-point perspective

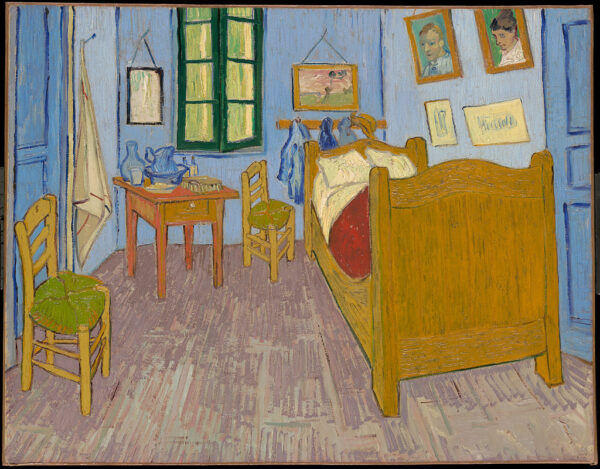

With one-point perspective, an image has been created to draw our eye to a single point. This is what is farthest away. The depth doesn’t have to be great—it can be as small as a room.

Which brings us to one of the most famous examples of point perspective: Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles (1888). This slightly claustrophobic rendering of his bedroom rushes towards the end point which sits in the window. The lines of the room are sharp and work almost as camera lens pulling is in.

Vanishing point perspective

Vanishing point perspective is often used interchangeably with one-point perspective, but this term is for an image that brings together every parallel line in the image to a single point that seems to disappear into the horizon. This form of perspective gives a sense of the view carrying on into the distance and out of sight, rather than ending at a single point.

Everything in the image gets smaller the farther away it becomes until there is just a dot on the horizon. Used in drawing more often than painting, point perspective is favored by architects and town planners, because it focuses on the sense of scale by converging towards a single vanishing point on the horizon line.

Is perspective just for landscape artists?

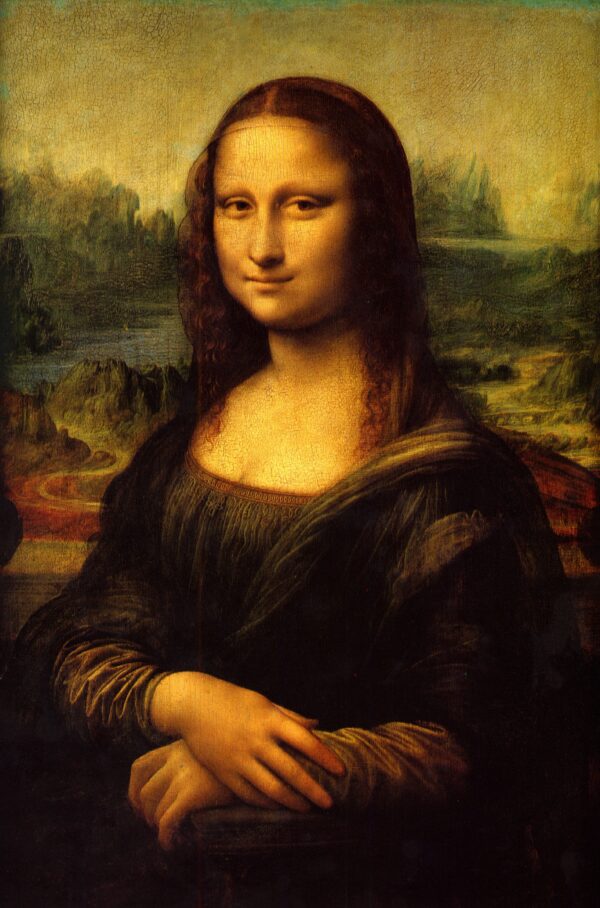

No! There was a time when a portrait was simply a head and shoulders with a blank wall of unremarkable dull color behind it. Although this style can be incredibly powerful (Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, 1665), artists began to furnish the backgrounds of their subjects using perspective to provide added interest.

One of the most famous examples of this is the Mona Lisa (1503). The face of an Italian noblewoman Lisa del Giocondo is the main feature, but behind her, a soft landscape draws the eye from her famously enigmatic smile to a distant bridge over her left shoulder. The bridge (which may or may not be from a Tuscan village) is a soft background, but a point perspective nonetheless.

How to draw perspective

For a masterclass in drawing point perspective, look to architecture. Architects take us through the spaces they have imagined for us and bring us to any point they wish us to observe and discern. It is a way of controlling and helping us adapt to abstract concepts such as a flat two-dimensional surface filling that space and creating worlds within it.

In fact, the master of perspective Raphael’s lesser-known second job was in architecture. In fact, he created the design for a chapel in Sant’Eligio degli Orefici, as well as the Chigi Chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo.

Using color to create perspective

Color also has its part to play in point perspective. Some colors recede, while others strike you immediately. A dominant color is the first color you look at: usually the primary colors, but also black and umber. On the other hands, a recessive color (most often tints and shades) is slower to draw the eye. In terms of perspective, the eye is drawn to the dominant colors first, before expanding out into the rest of the frame.

Abstract artists use color (and shape) in this way to create depth in their paintings instead of showing perspective. A dark umber (deep brown), black or even deep red will appear to sit behind paler tones. A colorist will use color and tone to play with perspective, optical artists like Bridget Riley use color to create works that actually seemed to move.

Of course, once you’ve learned how to do it, you can begin to play with the rules for artist license. Matisse’s Red Studio (1911) almost does away with perspective completely. The furniture and artworks appear to float on a flat sea of red. But each element of the room carries its own sense of perspective. The work shows how willing the eye is to see depth on a flat surface with only the slightest of visual nudges.