How do you write a good title for your artwork? And what does an art title mean? A memorable title becomes a work of art in its own right, and once you master the art of it, writing titles for your work can become a satisfying part of your art practice. Here are the key elements to consider when naming your work.

What’s in a name?

Giving your artwork a great title can make all the difference when it comes to how the audience perceives it. A good title pushes the themes or story behind a piece of work to the fore, allowing the viewer to make connections while leaving room for their own interpretation.

Naming your artwork is all about balance. Ideally, a title should gesture to the theme, inspiration, or concept featured within the work, without giving it away completely. The title should act as a prompt that tells the viewer how to approach the piece, giving them an entry point to access the narrative.

The right title draws your audience in

With the right title, you entice and enthrall your viewers, even before they’ve had time to process the work. You can steer them towards the direct meaning of the work, or push them towards obfuscation. A good title can set in motion a deeper and more complex appreciation of your work. It is how you set out your stall, your artistic intent. It can be a means of making a name for yourself, of establishing your brand.

Visit our blog branding, identity, and publicity – supercharge your art career to learn how to develop your own branding and identity.

Examples from history

Think, for example, of René Magritte’s famous painting of a pipe wittily named The Treachery of Images (This Is Not A Pipe). With this title, Magritte pulls into discussion the complexities of representation. It is not an explanation of the work, but a starting point. The title catalyzes further thought that propels the viewer back into the painting. Likewise, a good description will keep your viewer engaged by offering supplementary information that may not be apparent in the piece itself. Consider Johnannes Vermeer’s 1665 painting, Girl with a Pearl Earring which earned itself a novel and a movie around the girl featured. Another example is Van Gogh’s Starry Night. This extra information could make or break a sale, so it’s important to get it right.

In this article, you can learn how to increase artwork sales with a few small changes.

What comes first: the name or the artwork?

Titles are a necessary part of the fabric of artworks. They are a shorthand for a cultural cachet. Merely invoking these titles is to personify an identity as a knowledgeable and cultured person. Creating a title for your artwork is a vital part of the process of making art.

Many famous titles are not the original title specified by the artist? In fact, sometimes critics, curators and historians create a title long after the work’s creation.

Leonardo da Vinci’s La Gioconda became Mona Lisa, Frans Hals’ famous work was only named The Laughing Cavalier when it was exhibited at London’s Royal Academy in 1888. Picasso’s Le bordel philosophique (The Brothel of Avignon) became Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon), renamed by the exhibition curator to avoid upsetting exhibition-goers in 1912. Artwork continues to be renamed to reflect changing times. Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) was temporarily renamed Laure the name of the black maid who stands in the background of the painting for a recent exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

So whatever title you create, sometimes it is your audience who ultimately names it.

So how do you name a work of art?

Let’s look to history to explore different approaches to titling your work of art.

Obscure titles can work

The YBA’s (Young British Artists) of the 1990s were superb at titling artworks. None more so than Damien Hirst with his infamous Tiger Shark pickled in formaldehyde, the title of which is The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. For those that have witnessed this work, the title is perhaps the best thing about it. Other great Hirst titles include Mother and Child, Divided and I Want to Spend the Rest of My Life Everywhere, with Everyone, One to One, Always, Forever, now. If that isn’t a bombastic superlative I don’t know what is! His titles are resonant and weirdly efficient. Hirst’s one subject is mortality and mortality alone. How very Catholic. Even if you dislike his work, the titles draw you in.

The other YBA with a penchant for the snappy title is Tracey Emin. Her now lost tent piece with the title: Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995, showcased the appliquéd names of everyone Emin had ever shared a bed with in her life, inside of a regular store-bought tent. Other titles include the whimsical I Promise to Love You to the matter of fact My Bed. Both Emin and Hirst have one thing in common: a genius for self-promotion. Their work is personal, as are the titles of their work.

Literature can inspire great titles

For art titles, why not look to literature? Some writers seem to have a preternatural skill for titles. The American writer Carson McCullers is one of them. With titles such as: The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, Reflections in a Golden Eye, The Ballad of the Sad Café, The Square Root of Wonderful and Sweet as a Pickle and Clean as a Pig.

Borrowing from literary titles can also invoke a historical moment. American writer Joan Didion will always be associated with the title Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Taken from a poem by W. B. Yeats, the subject concerns the nascent Hippy movement in California circa 1967.

If you’re looking for a muscular title, look no further than the classics of 20th century American theatre. A Streetcar Named Desire, Death of a Salesman and Long Day’s Journey into Night. There is nothing squeamish in them. Their aim is to highlight their themes with a scathing ferocity and a laser sharp, artistic courage. These are not the works of dainty bourgeois evenings at the theatre. In the same way that the Impressionists paintings are no light-hearted, chocolate box, proto Thomas Kinkade, sentimental musings.

Exphrasis: borrow a title from a literary character

The Greeks had a word for a literary description of an artistic work: exphrasis. If writers can translate visual art into prose, why shouldn’t artists return the favor and use a literary title or character as the starting point for inspiration?

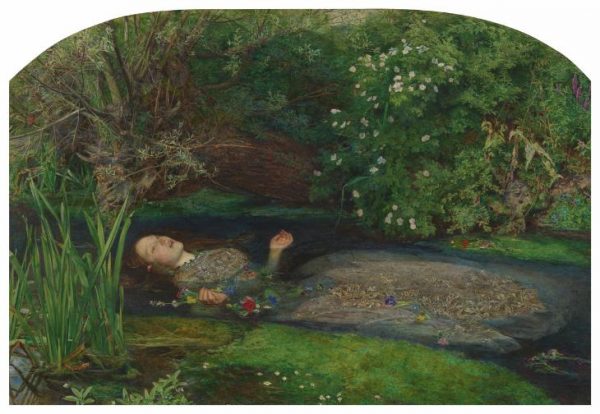

Some of the most famous examples include Sir John Everett Millais‘ Ophelia (1851-1852), named after Hamlet’s tragic heroine. In this case the painting depicts the character drowing, as she does in Shakespeare’s play. John William Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott (1888) depicts the character from Tennyson’s 1832 poem of the same name. The work doesn’t have to depict the subject matter directly. You would be hard pressed to find Alice in Salvador Dalí’s, Mad Tea Party (1969) a reference to Alice in Wonderland.

Simplicity

In contrast to the longer statement-like titles of the YBAs, single words can be very powerful. Edvard Munch’s famous painting Jealousy clarifies the relationship of the three figures in the painting. From just one word, we can distinguish each character. from the title of the artwork. The green face of Munch identifies him as the forgone lover, the woman as his love, and the second male figure, his rival.

Complex works don’t need complex titles. Just think of Nobel Prize-winning writer Samuel Beckett and his avant garde novels and their sparse titles: Murphy, Watt, Malloy, Malone Dies, How It Is, etc. If the titles seem needlessly simplistic and give a certain Celtic flavor to their charges, just try reading them. Good luck with that light bedtime routine. They’re among the most difficult books you will ever peruse, including the likes of Virginia Woolf and James Joyce. Beckett was no soft touch when it came to the intellectual. These novels are as much philosophical treatise as they are narrative stories.

Thought-provoking

The best titles for artworks can often be the least obvious. I still struggle to reconcile the title of the 1976 Martin Scorcese picture Taxi Driver with its content. Likewise, The Deer Hunter. The former about a rampaging, psychotic vigilante. The latter about the horrors of the Vietnam war. Both titles are fairly bland and revea little. Neither do justice to the unflinching violence captured within them. What could possibly be more dull than a film about a guy who drives a taxi all day? Both titles deliberately blindside the viewer.

Titles can be an effective tool to perplex the audience. Jean Luc Godard’s 1966 film 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her is most famous for its close up of a sugar cube in a cup of coffee that mimics the formation of galaxies. What does Godard’s title mean? It could mean everything and nothing. Godard continues to confound us and never really fulfills his title’s implied promise. Godard argued that for critics a work of art existed to confirm what they already knew, and that for artists it was a way of discovering what they didn’t know.

Why can’t I just call my art Untitled?

Untitled doesn’t mean the artist couldn’t think of anything else to call their artwork. At its best, it’s a title in its own right. Favoured by abstract expressionists, the “untitled” moniker has become less popular, perhaps because it is so associated with artists like Jackson Pollack and Wassily Kandinsky. It might be followed by parenthesis detailing color or a number in a series, but it has meaning.

For lesser known artists, choosing to name your piece Untitled is generally not advised. However, in certain cases, it may be warranted, especially in conceptual works where the absence of a label is considered part of the artistic statement. The minimalist Donald Judd, for example, used Untitled for many of his works to erase any trace of himself or his decision-making. For smaller, preparatory works such as sketches, a simple descriptive title should do the trick: Still life study in pencil 2020, for instance.

When Are Descriptive Titles Best?

With portraits or landscapes, it’s wise to use the name of the person or place as a title to provide context. When James Whistler came to paint his mother in 1871, he named the piece Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, a rather vague title for a portrait that has since come to be known by the more revealing Whistler’s Mother.

In abstract works, it is all the more important to provide the viewer with a “key” as a means of entry. When we approach Mondrian’s Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow, we can conclude that his interests lie in formal design and color theory. This assures us we can take the piece at surface level. Alternatively, the title of Jackson Pollock’s 1947 painting Lucifer reveals a dark energy at work, a beautiful angel who fell from heaven. The formal elements of the piece work together with the title to suggest a beauty in chaos.

Writing descriptions for your art

Writing descriptions can be another tricky skill to master. Descriptions should provide the viewer or potential buyer with the necessary background information beneath the work. A great description grabs the viewer’s attention, helping them to forge a deeper connection with the piece, which in turn increases the chances of a sale.

This longer explanation of the work typically resides within a catalogue or next to the image on your artwork. Sometimes, a description can help frame your work and lead to a title.

First you should consider your inspiration, the context behind the work. This could be a historical moment, a person, or a personal experience. Whatever it is, explain how you incorporated the essence of your subject into the work, be it through color, texture, or composition.

Anecdotes and Historical Context

A historical or personal anecdote can make a description memorable. For example, the Walker Gallery in Liverpool offers us an amusing backstory for Lucian Freud’s painting Interior at Paddington. The sitter of the portrait, Harry Diamond, was bitterly unimpressed with the artist’s depiction of him. He claimed the artist had made his legs too short, to which Freud replied, comically frank, “They were too short.” Background information imbues the work with narrative. Every time I see this painting now, Diamond’s sulky expression makes me laugh, as I imagine the pair squabbling during the sitting. Your audience is looking for something that grabs them, so while providing insight is crucial, it’s important to keep descriptions concise.

Keep it Brief

When creating a title for your artwork, you might want to consider a description of the work. Be economic with your language. Two hundred words is plenty when it comes to descriptions. Steer away from art jargon. Opt instead for clear, simple sentences, making sure that your tone is consistent throughout. If you refer to a historical period, art movement, or person, briefly clarify this with a short explanation. Never assume that your audience already knows.

The second part of a description is more straightforward. It should include the exact dimensions of the work, as well as all the materials used to create the piece, including the type of paper, canvas, board, etc. If your work is for sale you may also want to include information about your packaging and delivery services. For example, how will artworks be packaged, rolled, or stretched? What are your courier and shipping times? Though there is no perfect formula to writing descriptions of your works, these guidelines can steer you on the right path.

Further reading: How to write an artist statement

In conclusion: match the title to the medium

Now you are ready to write a title for your artwork. To prove the power of the title, below are some random title from works of art, literature and everyday life. Are they paintings or sculpture, photographs or drawings, films or books? Are they figurative or abstract? Or are they both? You decide.

A Circle and Two Virgins

Snow Storm on Santa Monica

Maisie Walking

Sunset: Solomon’s Peak

Untitled 1963

The Bastard

And As I Walked Through My Shadow The Ghost Spoke

Two Greens and a Blue

Jeff Sleeping

Gestural Mark No 3

Portrait of Blixen Brown

Le Bateau Lorelei, Moored and Anchored in the Harbour at Le Havre

Stephanie Curled up with Her Cat

In the Desert Nobody Remembers Your Name