What is more natural than the human body? Nude, the body is flesh wrapped in bone laid bare for the human gaze to contemplate. Is it any surprise that capturing the nude form has been the ultimate goal in art. What is it to be human? What is this creature conceived from dust and molded in flesh? How do we transfer the ineffable spirit of the human body into the stuff of chalk, charcoal, graphite, crayon, ink, paint, clay, wood, plaster, bronze and why?

Why are nudes important?

For any new artist, the ultimate aim in drawing techniques has always been the human form. In a life drawing class, students gravitate toward capturing the human body. Not only for artists, but for architects and designers. If you can render the human body perfectly in all of its complexity, you can draw any building, car, or ball gown.

If you wish to become a fashion photographer, for instance, studying the human body, producing drawings and paintings and even sculptures will absolutely, definitely, make you better.

A short history of the human body in art

In western art, at least, the nude has a grand tradition running from the ancient Greeks, through the Renaissance, to contemporary art with its myriad mediums and messages.

The oldest cave painting currently known in the Maltravieso Cave, Spain, is believed to be over 64,000 years old. Not surprisingly, the nude soon entered this very human technology of art. The Venus of Willendorf, which dates from 25,000 to 28,000 BCE, is the earliest preserved image of the human form. Its voluptuous curves evoke fertility and female power. But we can imagine that from the earliest history of art, totems to motherhood, childbirth and the beauty of the female nude probably existed.

Thousands of years later, the Ain Sakhri figurine, created 11,000 years ago in Israel, depicted the entwined bodies of embracing lovers. Equally, a number of highly stylised human figurines have survived from ancient Cyprus, produced around 3900–2550 BCE.

In the absence of written records, archaeologists and art historians can only speculate as to the purpose and inspiration for these objects, though in many cases they speculate that these nude figures served a ritualistic or spiritual use.

In classical Greece, a celebration of the idealized — but mortal — human body also emerges, with sculptors capturing the (frequently male) body engaged in athletic pursuits. The skill with which Greek, and later Roman, sculptors depicted the human form was matched by the beauty of the bodies that they chose to depict. That idealized realism remained the standard to which artists aspired throughout the Renaissance and beyond.

For a more complete history, check out our blog on the human body in art.

The male nude

Oddly enough, the nude we most identify with the Renaissance is the male nude. Michelangelo’s David stands seventeen feet tall and still, to this day, is our idealization of the perfect male physique. Anatomically perfect, with macho daring and a seemingly arrogant insouciance, David is every bit the hero, the warrior, the lover, the Man/God of western hubris. It is an overwhelming sculpture in the flesh and not a little homoerotic (Michelangelo’s sexuality is a matter of debate, which in itself, is of no real consequence to us). We are meant to stand before David in awe of his form and the artistic prowess of its creator.

This is no shrinking violet of an art piece. It is big, it is brash and it is bold. T he quarterback made art. It is also sublimely beautiful. Only Michelangelo’s Pietà in the Vatican in Rome rivals its elegance. The sorrow on the face of Our Lady and the repose in death of Christ, would break even the hardest of atheist hearts. If you pass by this sculpture (even behind its bulletproof glass) and fail to weep, you have no soul.

For more on the male nude in art, read our blog on the male nude in art today.

The female nude

The sexiest female nude in all of the history of art is Manet’s masterpiece Olympia. Manet created this large painting in the 1860s, and modelled after Titian’s Venus of Urbino (itself no slouch in the nude, or sexy department).

A naked woman stares out at the viewer, unashamed and adorned, in the accoutrements of a contemporary sex worker. The Parisian public of the time would have had no illusions about her profession. Olympia reclines on the bed, arrogant, alluring and voluptuously fecund. As though she were sent down to earth by an alien species to repopulate the planet.

You can virtually smell her skin, her perfume, her toilette, her sex, which she discretely covers with her hand. The image in all its full glory is sensual today, but seemed pornographic to a 19th century sensibility.

Of course, the most shocking and problematic element for today’s viewer, is the attendance of a black maid holding out a bouquet of flowers for Madam: she awaits her response, solicitous and ignored.

The female artist

In a genre so focused on the female body, it is strange – but not surprising – that female artists are all but missing from the history. British artist Dame Laura Knight made history when she attended her first life drawing classes in the early 20th century. Her subsequent work Self Portrait with Nude in 1913 caused controversy, with one critic opining it didn’t belong outside of her studio. The Royal Academy rejected it for show.

The body as a canvas

Finally, in the mid-20th century, a number of performance artists such as Carolee Schneemann began to reclaim the female form in art. They utilized their own bodies as both subject and medium, and as a tool to challenge political and art historical norms. Unsurprisingly, they were often greeted with public disgust and opprobrium.

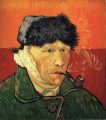

The self-nude

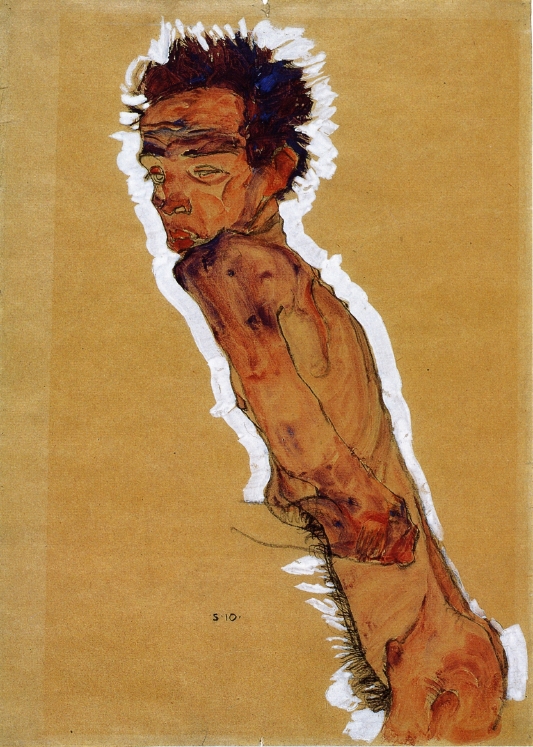

A rarity in the history of art – at least openly – many consider the self nude the height of technical accomplishment (and artistic bravery). Lucien Freud disavowed a nude of himself, which sold at auction after experts largely authenticated it.

Egon Shiele painted himself nude in 1910 and several times afterwards. Equally, British artist Jenny Saville broke through into the artworld with her self portrait Propped, painted in 1992, which shatters representations of female beauty (and later fetched more than $6 million at auction). Many other artists may have used their own bodies as unacknowledged life models.

Want to learn more about the nude self-portrait? Read our blog on the history of this brave art form.

Selling nudes

Nudes sell well at auction. Amadeo Modigliani’s Nu Couché (sur le côté gauche) sold in 2018 for $157 million dollars. Not bad for an artist who died aged thirty-five of tuberculosis, a penniless alcoholic.

Nu Couché (sur le côté gauche) has certain similarities with Manet’s Olympia and indeed with Titian’s Venus of Urbino, but Modigliani’s nude has her back turned to the viewer with her derriere in full view. She is more modern, minimal and austere. As with those other nudes, she returns our gaze. Her gaze, though, is less comely and more confrontational. You are there to do her bidding, not the other way around.

The modern nude

David Hockney returned us to the male nude in the 1960s with pictures like Man in Shower in Beverley Hills and Peter Getting out of Nick’s Pool. These are naked portraits of men, usually in, or near water. Their subjects prefer swimming pools and showers. Whether there is any symbolism in that is up for debate.

While Hockney is openly gay, there is less of an overtly sexual nature to these images. Certainly, the artist and the viewer can enjoy the beauty of these men, but they appear less sexually inviting than the previous female nudes mentioned. Of course, Hockney painted with a cooler style, which may create a distance that desexualizes them.

In contrast, Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs celebrate the erotic pleasure of the naked male form. His models are strong, flawless and fully ripped. They embody the pure essence of male beauty, and they exist for the viewer to admire and covet them.

Capturing the nude today

The nude is a staple in art and for good reason. To capture a powerful rendition and reproduction of the human form is the pinnacle of artistic skill. It turns the artist into the ultimate creator: a kind of God.

It is also fraught with moral traps. Who is on display and for what purpose? Are we to ogle lasciviously after the model on display (usually, but not exclusively female)? Did the artist exploit the model or cajole them into disrobing? Did the artist treat them with dignity? Or pay them fairly for their efforts?

There is a scent of exploitation which emanates from the nude in art. Further, the #MeToo movement and our contemporary understanding of the potential power dynamics in gender and sexuality render us less comfortable with the representation of nudity in art today.

As Amanda Jones (Lea Thompson) says tauntingly to Eric Stoltz’s character, in the John Hughes comedy Some Kind of Wonderful, of her portrait hanging in an art gallery. “What’s hanging in that museum, huh? My soul?”