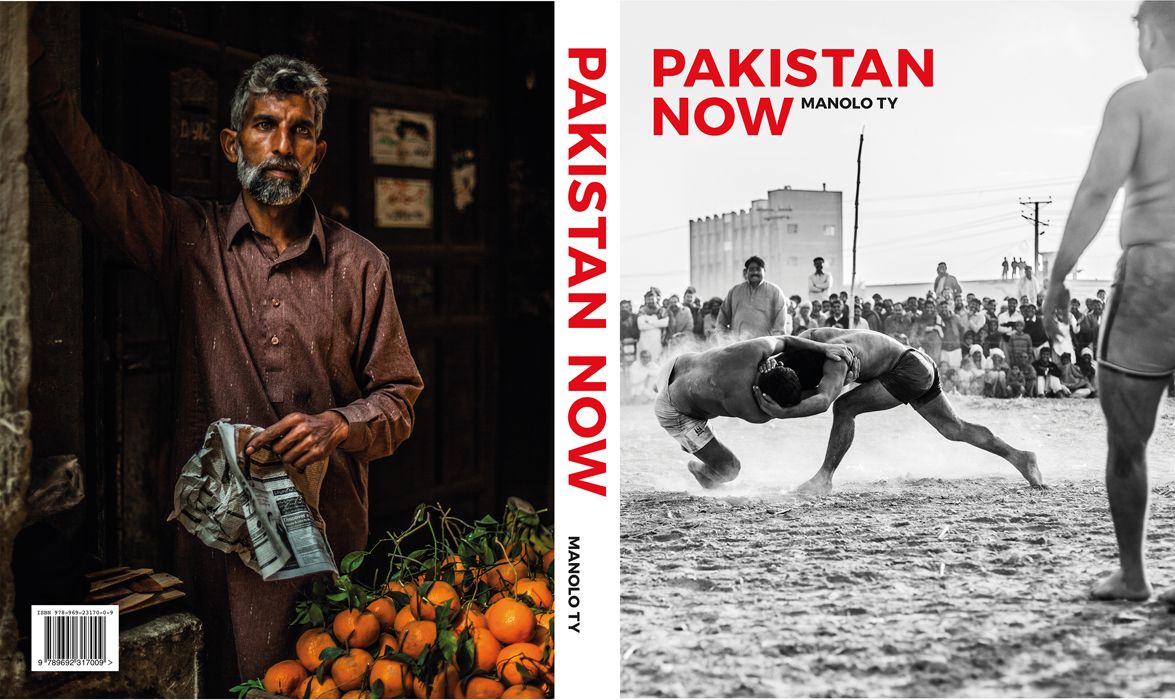

Manolo Ty is a tireless traveller and photographer, based in Berlin. After working in television and film, hospitality, and ending up on a boat full of passengers trying to escape society, he travelled to Pakistan with a camera and single lens. ArtWeb was lucky enough to talk to Manolo ahead of the publication of his new book, Pakistan Now, which unveils the fruits of this trip and the encounters he faced, in fierce and beautiful detail.

Artweb: You grew up in a very industrial area in Germany; did this affect your photography work?

Manolo Ty: It definitely affected me because I knew I wanted to get away and do different things. Every time I travelled I saw beautiful things, but at home it is was very grey. It is not so industrial now, but it is becoming a little like Detroit – businesses are closing and the whole place seems emptier. It definitely motivated me to move around and see new things. The first time I left was for about a year while I was Thai boxing training and working in film and television in Bangkok; I came back home and became depressed after three days. After five days, I left for Cologne. My hometown seemed very narrow-minded. I was developing a very liberal world view and that just wasn’t there when I came back.

AW: When did you start travelling? Was this when you were competing in martial arts?

MT: The competitions around Europe were probably my first travels. I didn’t get into martial arts because of the travelling, but it certainly opened my mind. It was great to see different cultures and the different ways people lived. Obviously, I didn’t have the option of travelling alone – I was still at school – but I knew as soon as I had finished school and military service was done, I would be gone.

AW: Military service?

MT: It was compulsory at the time in Germany. I spent 9 months in the tank division. In some ways, it was fun to ride around on 70-tonne monsters. But other ways it wasn’t. I realised that I didn’t like mindlessly following orders without questioning why; it cured me of ever doing that again.

I think it also helped later on while travelling because I knew how military structures worked. For example, I was in China before the Olympics opened, taking photos of the Birdsnest Stadium. It was (supposedly) complete but it wasn’t open yet so I climbed a fence to see it. Suddenly, the military was shouting at me and pointing a gun but I knew the soldier couldn’t leave his position, let alone shoot a foreigner! I just walked right up and took the photos I wanted.

AW: And how did you end up working in hotels?

MT: That really came out of nowhere. I was originally planning on becoming a film director and had been working in German television. Then I moved with my then girlfriend to Hungary and lived in Budapest but because of the language differences, I couldn’t make filming work there. After a couple of photography jobs – the Beijing Olympics for instance – I wanted to work on an idea I had called ‘Eco Nature’. Basically, I wanted to show that you didn’t have to destroy nature and build big concrete blocks to make money. You can build smaller, more ecological buildings and run a business without destroying the natural environment. But I didn’t know anything about hotels or hospitality; I was very naïve.

I went to the library every day and researched how to write a business plan, drafted a letter to the owner of the newest, most luxurious hotel in Hungary and told him what me and my ex-girlfriend could do what he was doing, but better. I wasn’t expecting a response but he said: ‘that sounds great, go ahead!’. So, at 23 years old we were running a hotel. I thought I knew everything I needed to know after a year and planned to set off on my own. But then the Lehman Brothers thing [2008 financial crash] happened and all investment was dropped.

I felt like I had to get away and wait out the crisis so I headed for Central America because they have some great models for ecological travel and hotels.

Then my passport was stolen so I ended up on a ship.

AW: It seems quite ironic that your passport gets stolen and you end up going travelling.

MT: Well I had a temporary passport but it was quite complicated for my girlfriend because she was Hungarian and the closest Hungarian embassy was in Cuba. With the temporary passports we couldn’t enter the United States for our return flights, so we thought ‘fuck it’ and headed for Colombia. The cheapest and easiest way of getting there was by sea and we ended up on a ship for couple of months. A French guy wanted to escape society and just lived on this ship. At the time there were seven of us.

AW: Like a commune on water?

MT: It was. We fished for our food every day and traded with the indigenous people on small islands so that they would let us stay for a week or so. I suppose this made me realise that you just have to do what you want in life; don’t run behind the money.

AW: Did you feel like a pirate?

MT: We weren’t pirates but that ship was attacked by pirates about a month after I left. They were the real deal with machine guns and stripped the place clean.

After some psychological issues, the Frenchman carried on sailing.

AW: With television production and film direction on your CV, it sounds like you are, fundamentally, a creative person.

MT: I am creative but I never thought of photography as a job until I was commissioned to photograph the preparation of the Olympics. I was 16 when I decided I wanted to be a film director but for some reason I never thought of ‘photographer’ as a job.

I come from a very working class family and was quite detached from culture as a child. It was never the case that creativity was something you could make a living from or call a job. My grandparents still think I’m on holiday even though I have been working for 10 years now.

AW: You have run a hotel and photographed an Olympic games; you have a been a crew member at sea. When did you dedicate your career to photography?

MT: Right after my time on the boat, actually. I asked myself whether or not I wanted to continue my ecological, natural hotel (which still had a good mission), but I still saw it as me running behind the money. I knew deep down that working in hotels or making easy money wasn’t what I really wanted to do. When you do that, you end up spending money to compensate for the fact that you aren’t living your dream. I didn’t want to go into book shops and look at the travel books, wishing I was there or wishing that I had taken this or that photo. Instead of watching documentaries about people doing crazy things, I was going to be that guy; I knew I would make it work.

AW: You became a full-time traveller and photographer.

MT: I had been travelling – or at least going on long trips with a camera – since 2006. I never put my camera down but, like I said, I never really considered it a job. All my pictures from this time, whether published or in galleries, were just given away.

It was only later that I realised that there was something in it and that all the work that goes into making a picture was part of the job description of being a ‘photographer’. I knew it made me happy and I went with it. I still am.

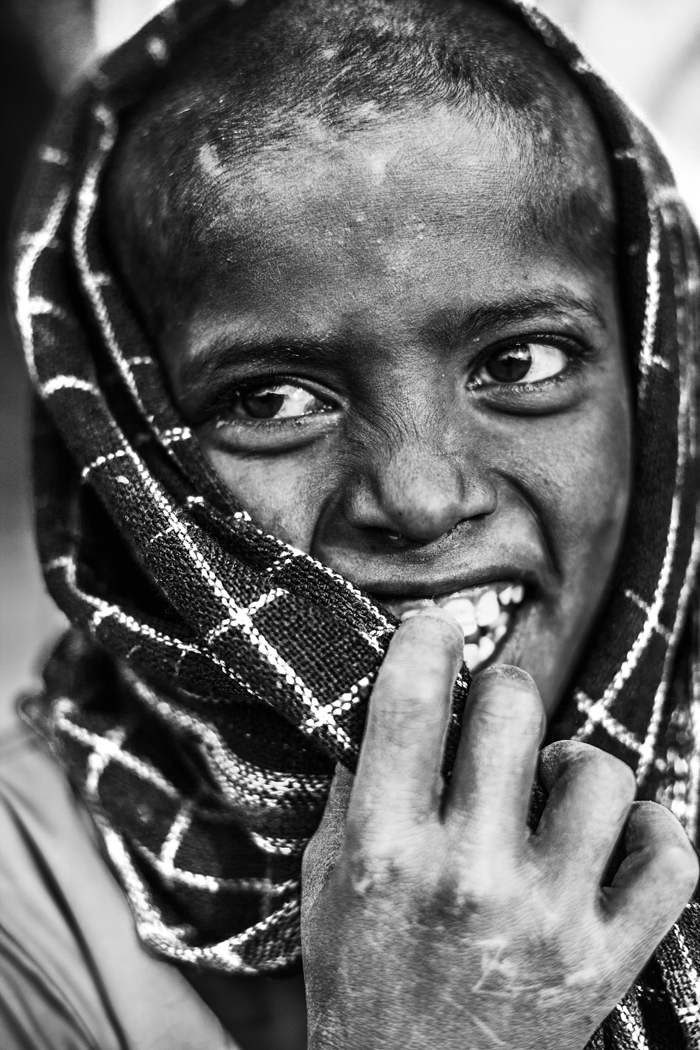

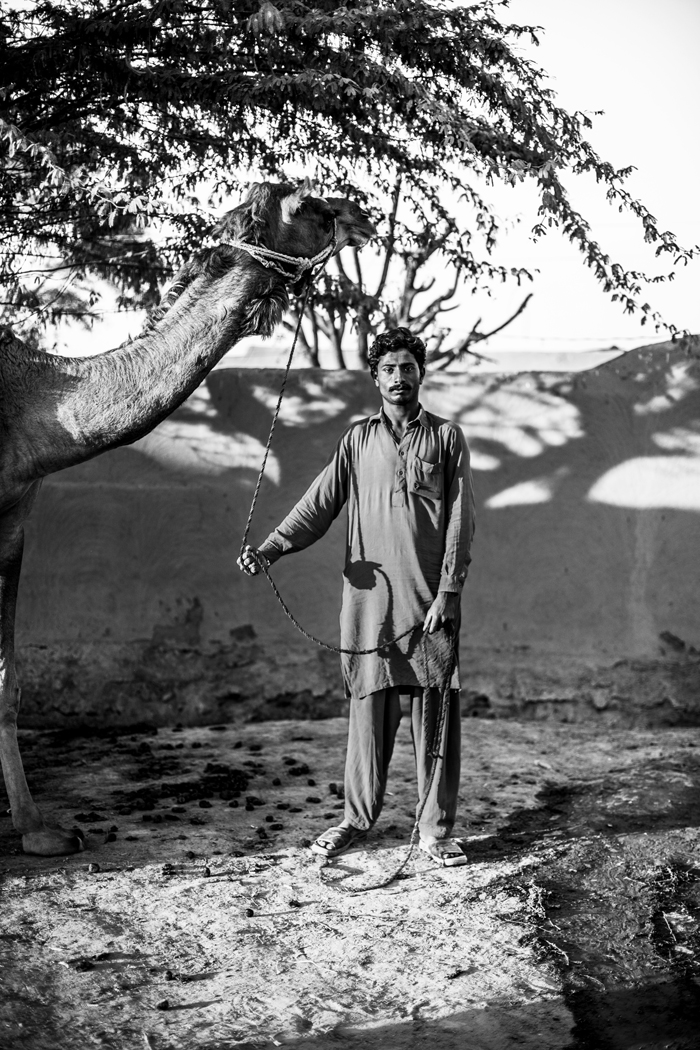

AW: You work alone, without an assistant, and take some very personal portraits. How do you approach your subjects?

MT: Some photographers sneak up and take photographs but I don’t want to be that guy. I just use one lens – a 50mm – so I have to get very close to people; I have to approach people and talk to them. It is hard for me to approach people I don’t know so I force myself to by just packing one, very close, lens.

I also think that this is a fair way of photographing because you are being honest and people know there is a photo of them out in the world. If you approach people who don’t want to have their picture taken, then they will tell you not to. But when you start a conversation, people see that you have the right spirit, and are usually very accommodating. Sometimes I don’t even approach people with my camera; I might talk to people for one or two hours before asking if I can photograph them.

AW: Do you have any stand out stories?

MT: There was an old lady from Nepal who lived in a little village that was at the exact epicentre of the [April 2015] earthquake. This photo (above) was taken almost exactly one year before that earthquake. For me it is a nice picture because she didn’t know any English or German, I didn’t know her dialect of Nepalese and yet we communicated, somehow. I gestured, asking her to take a photo, and this came out. Looking back, it is an iconic photo to me because it shows what used to be, what was destroyed.

AW: You mentioned that you usually have a mission when you work. What was the drive behind travelling to Pakistan for your new book?

MT: When I started travelling, I knew nothing about Pakistan. I would ask every traveller (some of whom had been travelling their whole lives) the most special place they had seen; everyone said one of two places: Iran or Pakistan.

After I decided I was going to go, started to do some research, but it was hard. There isn’t even a Lonely Planet guide to Pakistan! Some of the most recent books were from the 1990s and I think Lonely Planet stopped their guide in 2008. As for photobooks, nothing really covered Pakistan except for one book with 100-year-old photos.

I went with hardly any expectations except for the fact that everybody had said it was cool. As soon as I landed there I knew I had to do a book to change the perception that the media portrays. The drone war, ‘I am Malala’, Bin Laden, and polio is all you hear about and it isn’t reprehensive of the positive country it is. Nowhere on earth showed me the hospitality that Pakistan did; nowhere even comes close. I wanted to be objective because when you read stories and news reports, you don’t really have any idea of the beautiful landscapes or even how many people live in Pakistan. Before I landed in Pakistan, I thought it would be desert, but it is very close to how people imagine India, which has the advantage of a great marketing campaign for tourism. The biggest difference [between India and Pakistan] is religion.

AW: Without any in-depth books on Pakistan (or even specific aspects such as architecture, landscapes, etc.) you had to document everything in one book.

MT: I would never say that my book shows the whole country because Pakistan is huge. It is two and a half times the size of Germany, so I mainly focused on showing the culture through people. I photographed people in the areas in which they live to show how diverse a country it is. I hope that people can see how hospitable everyone is; I have been to nearly 100 countries in the world and no one has been as welcoming as those in Pakistan, especially in the border region with Afghanistan. If someone builds a house there, they build two houses! One house is for them to live in and other is for guests – and everyone is a guest. For example, if you are walking past then you can stop and stay there and you will get shelter, food and protection. Sometimes this is used by terrorists because there are no questions asked and the terrorists know they will get protection. If you are American, English, German, or whatever, when you stay there you are staying under their hospitality law. To me, this blew my mind: imagine going to London and being able to stay in a stranger’s house.

AW: People don’t even talk on the bus in London!

MT: I know, crazy.

AW: So, are you are back in Europe and settling down in Berlin?

MT: I made Berlin my base in 2010 but I will always travel and end up back here. Berlin is a good place because there is a good art scene and culture in every form. As for travel, is it easy to get around. I really like being here.

Manolo Ty’s new book, Pakistan Now, is now available to order. See Manolo Ty’s website for details on how to get your copy.