For centuries, egg tempera was artists’ preferred medium for panel paintings, and many medieval and Renaissance masterpieces found in museums and art galleries were executed in egg tempera.

More durable than oil and with a luminosity similar to watercolor, egg tempera offers many advantages to artists willing to embrace the challenge of working with this ancient medium.

Artists mix their own colors using dry pigments that are still available today.

Does egg tempera actually have egg in it?

Yes. Egg tempera is created by mixing egg yolk with powdered pigments and a little water. Traditionally, tempera was applied to wooden panels, such as poplar, coated with a special primer called gesso.

Why egg?

Since the dawn of painting, there has been an age-old question: how do you get pigment (color) to stick to a surface? The answer is to create a binding or glue that fixes the pigment to that surface. Untreated porous surfaces, like paper, canvas and wood will absorb the fluid, leaving the paint pigments alone and vulnerable to flaking off. While non-porous surfaces, like the aluminum being used by modern artists, can peel.

So the surfaces needed priming with something that would do its bit to create the ideal surface. Traditionally, tempera was applied to wooden panels, such as poplar, that were coated with gesso (a primer made from rabbit skin glue) and (usually white) pigment. Many artists continue to use this ancient recipe, and luckily vegan alternatives are available.

As anyone who has ever baked will know, the egg is a peculiarly sticky substance that indelibly binds together ingredients. This ability was harnessed by painters thousands of years ago. Mixing fine powdered pigment with egg yolk created a strong bind.

Why do artists use egg tempera?

Ask any artist and they will tell you the greatest appeal of egg tempera is the glowing quality that made it ideal for Renaissance painters who wanted to capture ethereal biblical scenes.

Tempera is more transparent than oil and holds less pigment. This lets the light penetrate through it and reflect off the white surface of the primer beneath it. Another advantage of egg tempera is that, unlike oil paint, it is resistant to light, and its colors do not darken or change with age.

But egg tempera doesn’t always work. Leonardo da Vinci used it—alongside oil paint for The Last Supper. His combination of egg tempera and oil paint onto a dry ground of chalk bound with glue created an unstable surface soon after completion. Normally, a fresco was painted directly onto wet plaster. Today there have been many efforts to save this priceless work, including some ill-advised restorations.

How is egg tempera different from oil paint?

Tempera cannot be layered in the same way as oil paint, and cannot be used to build impasto (texture). It also dries very quickly, meaning that artists must work on a small area at a time, using small strokes and cross-hatching. This makes it best suited to fine, detailed small work using fine brushes, such as portraits.

Unlike oil paint, tempera easily washes from paint brushes and clothes since it’s mostly egg yolk. But the pigments in the paint may stain, so wear old clothes anyway. Egg tempera also lacks the noxious chemicals that go with oil paint, such as strong-smelling (and extremely flammable) solvents like paint thinner and turpentine.

How is egg tempera different from acrylics

Acrylics are water-based paints that have become immensely popular with artists and hobbyists in the last century. These paints boast vibrant colors and dry extremely quickly. They come ready-mixed in a rainbow of colors and are considerably cheaper than oils. Like tempera, acrylic paint tends to be flat, and layering is used to create a depth of color rather than texture.

Acrylic can be used to create a sort of glow using scumble techniques. This is a small dry use of (usually) lighter pigments on top of darker colors.

The history of egg tempera

Egg tempera was used in the ancient world, including in the famously lifelike Fayum mummy portraits, produced in Egypt from around the 1st century BC to the 3rd century AD.

In the early Christian era it was used to paint icons—a tradition that has survived in the Eastern Orthodox Church until today.

Egg tempera was also used to decorate the interiors of churches and secular palaces in fresco. It became commonly used in the 14th century when Flemish artists such as Jan van Eyck (1390–1441) used it on small-scale panel paintings. But Flemish painters soon moved on to oil painting which has dominated art for more than 500 years.

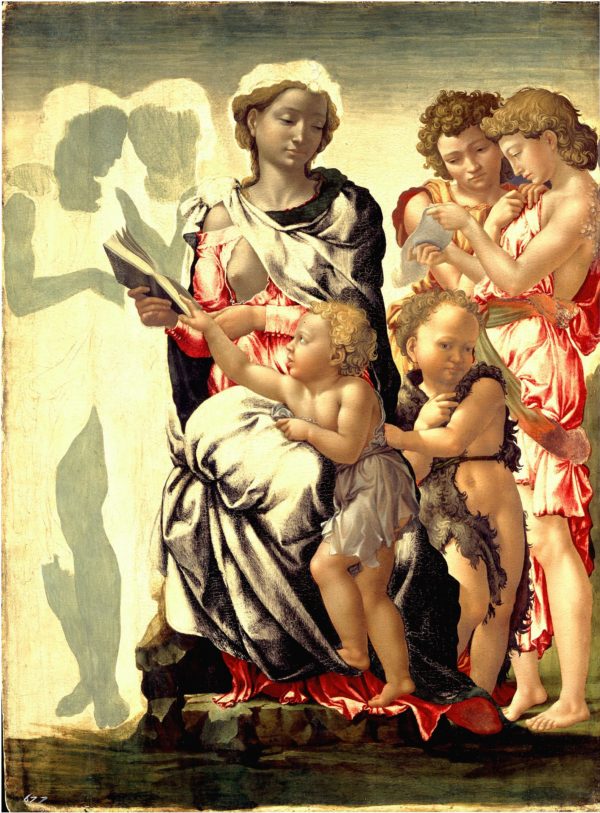

The work of Michelangelo (1475–1564) brilliantly captures the turning point in Italian Renaissance art as painters switch from egg tempera to oil paint, the medium preferred by their northern counterparts. In the National Gallery, London, visitors can usually observe two unfinished works, the Manchester Madonna, painted in egg tempera in around 1497, hanging next to The Entombment, painted in oil in around 1500.

From that time onwards, oil became the dominant medium until the 19th century, when egg tempura was once again adopted by the Pre-Raphaelites, who sought to return art to a perceived state of purity found before 1500.

Why do modern artists use egg tempera?

Many artists like the idea of preparing the surface and the paints themselves, which tempera lends itself to (see our recipe further down). But it is also available ready mixed in tubes and jars.

As the oldest paint medium, it also has a proven track record of longevity. Artists can see how their work will look in hundreds (and potentially thousands) of years.

Which modern artists use egg tempera?

While egg tempera has never been used as widely as it was until the High Renaissance, a number of 20th-century artists adopted the medium as their own, including Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978), Stanley Spencer (1891–1959), and Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009).

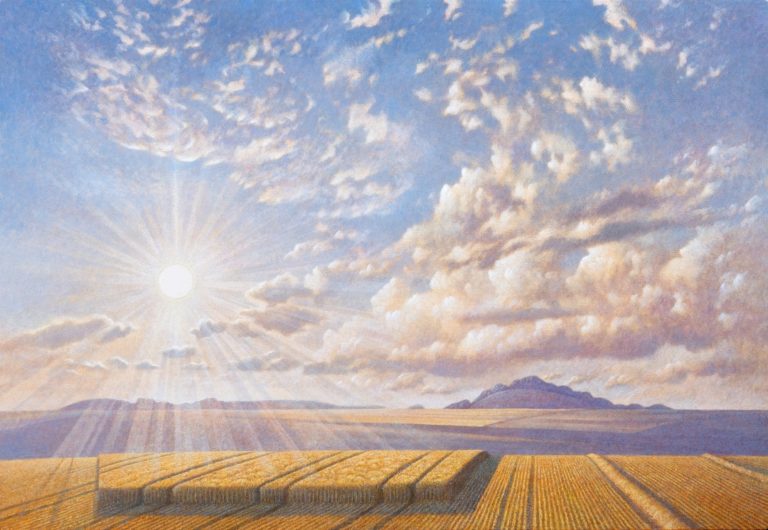

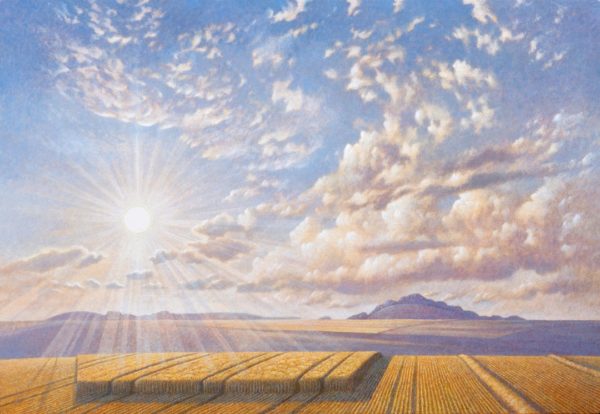

One artist inspired both by the medieval masters and by Wyeth is the contemporary painter James Lynch, whose light-filled depictions of West Country skies and landscapes are highly sought after by collectors.

Lynch originally painted in oil or watercolor, but after teaching himself to paint in tempera using the 15th-century handbook written by Cennino Cennini, has now been working in the medium for over twenty years.

Image courtesy of and copyright James Lynch. | Photo by © James Lynch

“I was always impressed by the strength of color and the glow of the medieval tempera paintings in the National Gallery. But I also loved the chalky layered subtlety of Andrew Wyeth’s paintings,” Lynch explains. “I felt that I’d pushed gouache and watercolor to its limit and needed a change. I love the fact that I’m painting with a living medium, egg yolk, which literally gives life to the paint. It has a waxy feel to it, and starts to set as soon as it meets the surface. It’s a matter of building up layers of glazes to gain a rich surface. The more one puts in, the greater the reward.”

Lynch also enjoys the feeling of self-sufficiency that working in egg tempera provides, keeping his own hens to provide the steady supply of eggs that the medium requires, and preparing every part of his paintings by hand.

Tempera sticks

This is a quick mention of these modern inventions that bear an uncanny resemblance to crayons. The colors are bright, and they are great for blending with fingers. They generally dry in a couple of minutes, so you still need to work fast. It’s also easier to find tempera sticks without eggs. They are mostly marketed to children and untrained artists, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t give them a try!

How to make egg tempera paint

The surface is part of the recipe when painting with egg tempera. Your list of ingredients are:

- Panels: poplar was most commonly used by Italian Renaissance artists, and is more durable than MDF (medium-density fiberboard)

- Rabbit skin glue and whiting, to create the gesso ground for your painting

- Egg yolks, carefully separated from the egg white.

- Pigment powder: Sennelier is the most famous supplier (used by Chagall). Or you can play with liquid dyes like food coloring.

- Soft hair and bristle brushes

- A ceramic palette for mixing

Recipe: How to mix egg tempera

Step 1: Carefully puncture the egg yolk over a glass jar, and discard the membrane.

Step 2: Add an equal amount of water to the egg yolk, and stir.

Step 3: Mix the liquid with powdered pigment on the palette. Note that egg tempera dries quickly, so you will need to prepare new paint each day.

Is there a vegan or vegetarian alternative to tempera?

Rabbit glue is traditionally used to help the paint bind to the surface and is made from boiling rabbit skins. There are alternatives that are used to prime most modern canvases. At one time, rabbit skin glue was considered the best surface for oil painters, but that has long been replaced. Use an oil-free gesso and yolks from free-range eggs.

Can you make a tempera without eggs?

The egg yolk is the fast-drying element of tempera. But it is also what gives the traditional glow to the paint, this makes it difficult to match with other ingredients. Some artists will substitute the egg for gum arabic created from tree sap, also used in watercolors and gouache paints.

If you are vegan or have egg allergies, switch to acrylics using a fine brush, and add a very thin transparent glaze once dried. This will bring out the luminosity of your paint colors.

Where can I learn more?

In the UK, The Royal Academy often runs short courses in painting in egg tempera. In the USA, The Society of Tempera Painters lists upcoming courses.