Joseph Cornell had a huge exhibition displaying 80 pieces of his work in 2015 at the Royal Academy in London. Within the art world he won the admiration of Marcel Duchamp and Robert Motherwell. Among art collectors, his assemblage boxes were snapped up when you could get hold of one. Cornell was notoriously reclusive; he never left the US and he rarely let a male into his studio.

It will come as no surprise to hear that Peter Blake continues to be a fan – owning one or two of the famous boxes himself. However, at a recent talk Blake gave at the Royal Academy with Tim Marlowe, I was slightly taken aback by the fact that Blake and Cornell shared a patron in the form of Tony Curtis.

Curtis, apparently a notorious skinflint in Hollywood, certainly had an eye for art and even liked to open his wallet every now and then for the cause.

Above his desk in his Los Angeles study, Blake recalls a beautiful Cornell box. Blake later found out that Curtis had produced that one himself.

This type of flattering appropriation is nothing new: for years, in the moulds of others, artists have retraced the strokes of genius in an attempt to understand the works of their idols more fully. Hunter S. Thompson repeatedly retyped Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby on his typewriter to understand the prose’s idiosyncrasies, the canter of the language as it tumbled forward and how the fingers sprung from one word to the next.

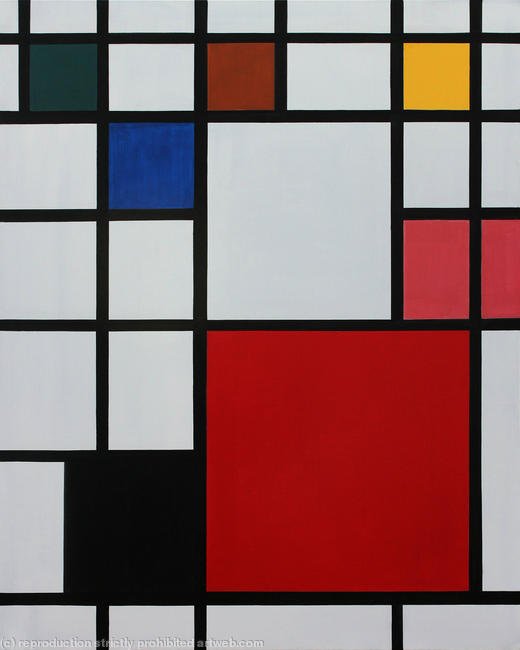

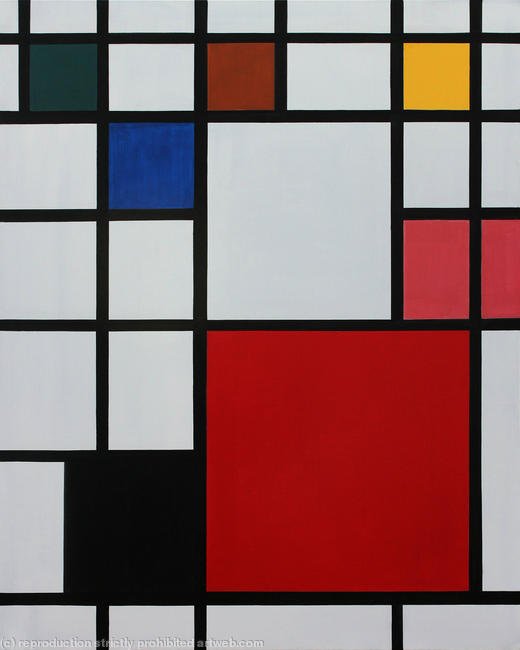

Working in the vein of someone else allows you a certain amount of interpretation and artistic licence. More than anything, however, it is a chance to recontextualise the work in question.

Visual images and works of fine art have always been tools for social comment. They become emblematic of a specific historical period but their power lasts into the present.

Princesse de Broglie, Ingres’s masterpiece, was taken as the medium of Turkish artist Taner Ceylan’s latest exhibition. Perfectly executed as a study in oil, the face of Ingres’s canvas was replaced by Ceylan’s own. Bringing the narrative behind Ingres’s painting – that the sitter was naturally very shy but was portrayed as the perfect hostess – into the present, the timeless themes that both works grapple with, the very nature of portraiture and selfhood, are given relevance on an even ground.

It is easy to consider appropriation fraud or mere ‘copying’. Reproduction in the arts has always been a bone of contention. There are artists who are actively working to dispel, or just complicate, this notion. Serra Tansel has reproduced her own works and destroyed the originals, making each copy its own reference. But really, artist appropriations offer much, much more than just a chance to trace their heroes.

Like Thompson, following the lines of Fitzgerald, freeing yourself from the pressures of creating something new through recognisable signs, you realise firsthand that the old saying that you can’t have an original thought is true of art as well.

The history of art is a history of comparison, an artists’ work doesn’t start its own history or staple something new to the end of art’s history as it is understood, it always happens in the middle as it constantly unfolds.