As Britain recovers from a summer in which many faced the threat of wildfires and drought, and which left London’s consistently lush green spaces sun-bleached, the realities of the changing climate have never felt more immediate. Many artists are reconsidering their practice to meet the stark realities of the moment, as familiar weather patterns become more erratic and fears loom that, without urgent intervention, life as we know it could be left radically altered in the coming years.

Environmentally engaged art has taken many guises throughout the course of art history. Land art— art that takes the earth as its subject— first emerged as a movement in the late 1960s in tandem with the broader social and political shifts of the era. The classical landscape art of the 17th century had come to seem quaint and old-fashioned to radical-leaning young artists at a time when post-war minimalism and the burgeoning conceptual art movement dominated gallery spaces. Otherwise known as Earthworks, process art, or ecologic art, land art engaged various media—most often sculpture, photography, or site-specific installations that sought to transform the relationship of the viewer to their natural environment. Works were often installed in remote and rural locations; artists were eager to break away from increased urbanization and the cultural monopoly major cities held over artistic production. Whether the result was totemic, large-scale pieces carved into the earth itself, or ephemeral, short-term interventions intended to mirror the ebb and flow of organic processes, land artists occupied a new terrain as they examined how a post-industrial world had altered the complex and increasingly fragile relationship between man and nature.

Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty and The Earthworks Movement

Perhaps the most iconic work of this era is Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970). Reminiscent of an unfurling fern frond, the 1,500 foot long spiral extends anti-clockwise from the north-eastern shore of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. Reaching 15-feet wide, it is formed of six thousand tons of soil and basalt rock. Smithson chose the location for its distinct ecological features. The lake is a terminal basin—what’s known as endorheic—meaning it is essentially barren and lifeless. The location stands in the shadow of unused oil rigs, ghosts of industry that loom over the fluctuating water levels of the basin. The high presence of algae in the water gives it a purplish tint (in aerial images the lake often appears a red wine shade). The basin is rich with salt-crystal deposits with a filigree-like texture that fascinated Smithson and which he took as his inspiration for the shape of the jetty. A visit to the Spiral Jetty is to experience it as an outlook, an invitation to fully embody the landscape and its shifting scale and dimension.

Women Artists in the 1970s-1980s Land Art Movement

In the nearby Great Basin Desert, Nancy Holt—who was married to Smithson until his death in 1973— created Sun Tunnels (1973-1976), four concrete cylinders reaching 18-foot long and intended to frame the movements of the rising and setting sun. Each tunnel contains a series of small holes that map select constellations, tiny apertures through which to view the earth’s rotations and celestial shifts. Holt was not the only female artist to contribute to the movement. Hungarian-American artist Agnes Denes (born 1931), considered a pioneer of environmental art, infused her work with social-political ideas. In 1968, she created Rice/Tree/Burial, a site-specific performance piece in which she sowed rice into a field in Sullivan County, New York. She wrapped thick, industrial chains around surrounding trees and buried a capsule of her haikus beneath the ground, to remain there for a thousand years. The rice represented sustenance, conception, and initiation; the chained trees spoke to bondage and human interference; and the poetry was representative of the abstract, creation itself. In 1982, Denes created Wheatfield: A Confrontation on a piece of landfill in Battery Park City on Manhattan’s southern tip. The two-acre field of grain was an act of protest, intended to highlight growing ecological concerns and widening economic inequality. The wheatfield would last only three months, but its lasting image is a striking juxtaposition— the clash of the natural with the man-made, a stirring rebellion against the imposing buildings of Wall Street that remain emblematic of modern capitalism.

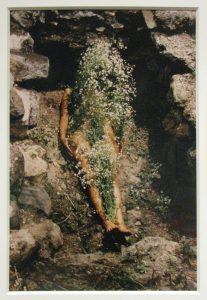

Cuban-born artist Ana Mendieta (born 1948) was inspired by visits to pre-Colombian sites in Mexico and Central America. She was drawn to pantheism and exploring feminine archetypes. In Silhueta (1973) she painted her silhouette into sand, carving the outline of her body into the earth, etching it into clay beds, sand formations and rock faces. She used organic materials like moss, branches, or flowers to outline abstract feminine figures. Mendieta termed her practice ‘earth-body-work’, and saw her art as a means to dialogue with the natural world; as an emigrant extracted from her native land, she sought to re-establish the bond to between self and habitat. She was eventually able to return to Cuba, carving feminine forms into limestone grottos in the outskirts of Havana, before her premature death in 1985.

The dramatic scope of the American West—with its deserts, mountain ranges, arroyos— provided a kind of spaciousness that invited large-scale creative thinking. Much of the seminal work of the Earthworks movement can trace its origins to prehistory—whether petroglyphs, Palaeolithic cave paintings, or Aztec stone sculpture; Robert Smithson was likely influenced by Native American serpent mounds and the Nazca Lines of Peru. The adjacent development of land art in the UK would take a different form, to meet the contours of the land itself.

Land Art in Britain 1970s-present

The Uffington White Horse is a mysterious, 360-foot horse carved into the Oxfordshire countryside, the grooves of its elegant limbs filled with white chalk. Some archaeologists believe the horse to be an example of a solar deity, a neolithic concept in which the sun travelled across the sky on a horse-drawn chariot. Like nearby Stonehenge, part of the allure the white horse, now 3,000 years old, is the mythos that surrounds its unknowability. British topography is dotted with land-based artefacts that likely held spiritual significance for Celtic and druid tribes, and were highly influential to British artists of the early land art period.

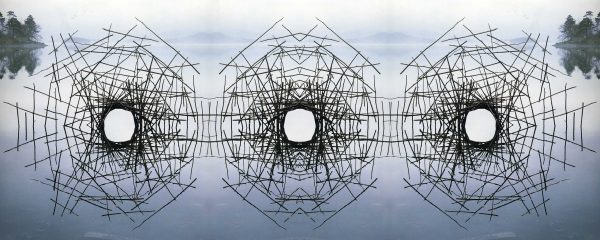

Andy Goldsworthy (born 1956) creates contemplative work sensitive to the temporal features of the land. Using found materials— feathers, pinecones, icicles— he creates formations that serve as meditations on natural rhythms. In 2003, Goldsworthy created Drawn Stone in the de Young museum in San Francisco using imported sandstone from his hometown in Yorkshire. He took a hammer to the rock to create unpredictable breakages reminiscent of the fault lines of the city itself. The lines were minimal, discrete, and often went unnoticed; the work captured the subtle, slightly ominous mood that permeates a city which experienced one of the deadliest earthquakes in history and remains vulnerable to extreme tectonic shifts.

In 1972, English sculptor Hamish Fulton (born 1946) put aside his tools and took to the road. A self-termed ‘walking artist’ Fulton pioneered wayfaring as a creative act, using text, illustration and photography to trace his routes through the British countryside. The art is the journey itself. Fulton’s walks are a meditation, a ritual. Like Fulton, sculptor Richard Long explores walking as art form in A Line Made by Walking (1967). Through ritual and repetition, Long treads into the turf until new tracks and paths are formed in the landscape. An exploration of memory and wayfinding, his work recalls a minimalist, anti-materialist approach, a critique of the consumer-focused art-market.

Modern Eco-art in the Age of the Anthropocene

As we grapple with what it means to inhabit the so-called Anthropocene, a time of increasing geological significance, many artists are combining their work with political activism. In 2002, American artist Aviva Rahmani located four large boulders in Vinalhaven Island, Maine, and painted them blue. She considered the work an ‘ecovention’ intending to draw attention to an obstructed causeway on the Pleasant River. Her plan succeeded, leading local authorities to donate $500,000 to the restoration of the estuary. Pembrokeshire-based Jon Foreman takes the beaches of Wales as his canvas, creating striking, whorling patterns from various colourful flotsam. Dutch photographer Thirza Schaap takes a different approach to beach-combing with her series Plastic Ocean, using litter and waste she finds washed up on the shoreline to create striking, still-life compositions that illuminate the threat of over-consumption.

Icelandic-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson—best known for his Turbine Hall commission The Weather Project (2003) – in which visitors bathed in the warm shine of a large, glowing sun— has long woven environmental awareness into his work; he recently created Earth Speakr– an augmented reality app in which children are invited to design a CGI face which maps their expressions. Faces are then transplanted onto the earth’s surfaces, giving voice to their concerns about the environmental crisis and establishing a new awareness around coexistence, reciprocity and stewardship. Olafur Eliasson Studio recently committed to achieving carbon neutrality, including a no-fly rule in commission contracts to transport material, creating a template for other artists to do the same as they meet the demands of a changing world.