Art is rarely easy to classify. Whilst artists may spend a significant amount of time considering the benefits of presenting their work in a particular medium, it is common for many to develop and adhere to a niche of presentation. No matter if they’re known for succinct haiku or visually arresting collage, an artist breaking away from the medium they are best known for is newsworthy gossip. This leads us to a question: what of those works which use several artforms and techniques to tell a single, cohesive story?

Transmedia storytelling is the art of delivering an experience via multiple mediums and formats. The transmedia part of transmedia storytelling lies in its multitudes: the very nature of this form of art begets plurality. Whether you’re piecing together a fictional narrative composed of cryptic tweets and YouTube vlogs or combing through custom-built websites hunting for a character’s phone number, the transmedia genre thrives in complexity and innovation.

From incidental display to purposeful immersion

Despite its modern-sounding name, transmedia is not a new phenomenon. The genre has its roots in the 1960s Japanese practice known as media mix: a method of distributing content relating to a single property across several platforms. By delivering story-related content in the form of tie-in shows, video games, toys and more, media mix became an effective strategy for advertising intellectual property whilst allowing for the expansion of a given property’s universe. Today, we are familiar with the power of global franchises such as Pokémon and The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), but it was media mix which paved the way for the enormity of these properties.

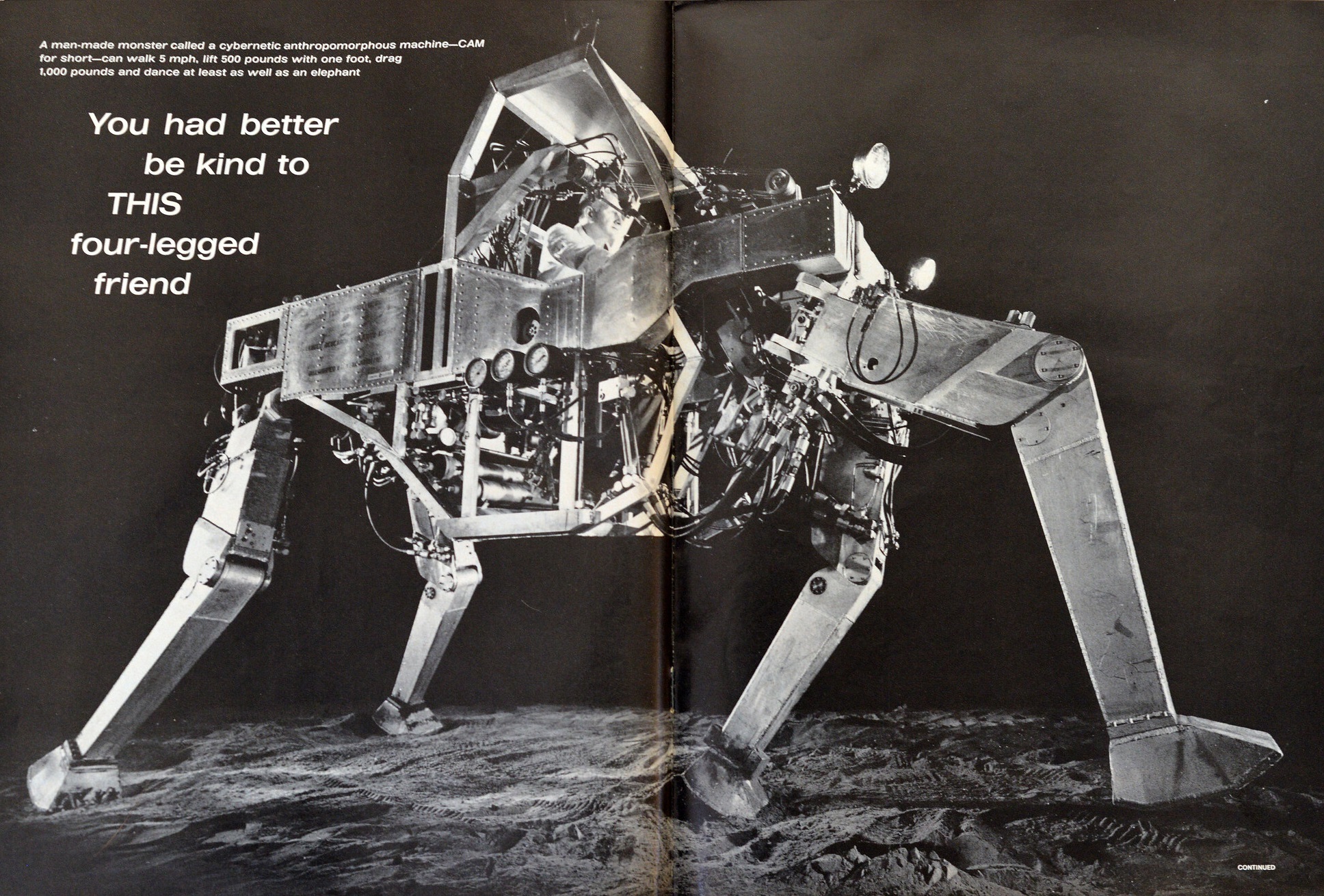

Armed with the knowledge of this history it is easy to assume transmedia to be devoid of artistic merit, and nothing more than another corporate advertising strategy. However, media mix paved the way for the emergence of interactive transmedia movements in the 1970s and 80s. Cybernetic art involves the use of electronic and digital feedback as a way of creating and examining art. Similarly, telematic art refers to the use of telecommunications as an artistic medium. In both of these artforms we see a growing interest in experimentation with new technologies, alongside the development of the role of the audience. Once observers and reactors to static, unchanging art, now the audience becomes an active participant in the creation of art by virtue of their responses. Today, cybernetic and telematic art are grouped under the transmedia umbrella. Both techniques caused transmedia storytelling to be synonymous with immersion, the use of cutting-edge technologies, and a responsive, collaborative relationship between creators and their audience.

Alternate Reality Games and the role of advertising

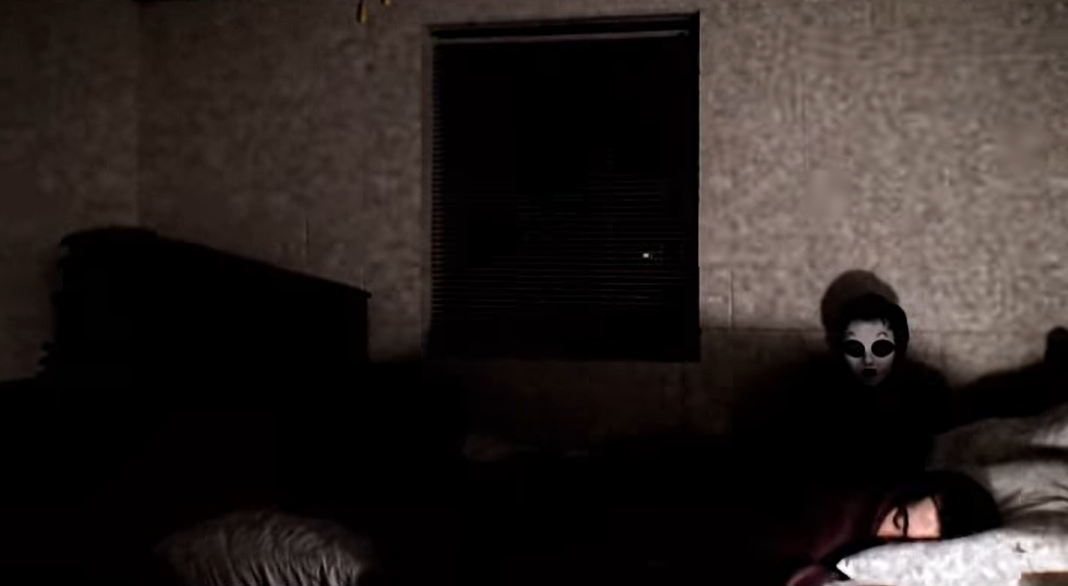

Of course, the story of transmedia storytelling does not end in the 80s. In the late 1990s The Blair Witch Project was released: a supernatural horror film which garnered positive responses for its use of the found footage storytelling framework. Found footage presents art as if it were originally made for a different purpose, and later discovered by another party. By presenting the film’s story as in-progress (and abandoned) documentary footage, Blair Witch constructs a veneer of reality which allows for further suspension of disbelief on the part of the audience. Yet, this blurring between fiction and reality does not stop at the filming. The marketing team behind the film produced a number of fake police reports, newsreels, and even a website detailing events from within the movie as if they were part of a true murder investigation. These tactics caused many to believe that they were in fact watching a real documentary, and coverage of true events. In this approach we see echoes of media mix, cybernetic art and telematic art as artistic predecessors. Instead of just presenting an onslaught of mediums to increase audience interest, capitalising on the power of telecommunications technology or directly involving the audience in the creative process, we see a project which actively attempts to make a story indistinguishable from our own reality…and this made The Blair Witch Project wildly popular.

Advertisers and artists alike took note of Blair Witch’s success. The 90s and 2000s gave rise to the Alternate Reality Game (ARG): a storytelling device which uses the real world as a platform. The founding principle of ARGs is T.I.N.A.G., or This Is Not A Game: the idea that one must attempt to preserve immersion for the audience at all costs. The use of technology, social media, blogs, actors, wikis, real-life locations, forums, games and more are all employed in the service of convincing those interacting with an ARG that they are experiencing something real. In 2001, the Steven Spielberg film Artificial Intelligence: A.I. was released alongside what is widely considered to be the first true ARG, named The Beast. Hidden in the credits for a trailer promoting the film was the name of one ‘Jeanine Salla, Sentient Machine Therapist’. Intrepid viewers who searched this name online ended up uncovering a layered narrative related but external to the plot of the film, using a system of websites to deliver fragments of information. In the true spirit of transmedia this information was not just delivered in a single block of text within a link, but instead required active problem-solving and collaboration for successful progression through the story. Not only were the audience being convinced of the reality of these events, but they became involved with the story itself, as if they were characters in a game.

The Beast was so admired for its scope and complexity that it spawned its own fans. The most active of these fans were a Yahoo group called The Cloudmakers: individuals aware of the fictitious nature of The Beast, but whom still participated in the fun of piecing together the story as if it were real. This group of Internet detectives pooled together their skills and resources in order to recover story-related clues left by the ARG’s marketing team, effectively reconstructing a deliberately deconstructed story. With this dynamic came the advent of an entirely new form of transmedia storytelling, redefining the roles of artist and audience and blending them together as one, interactive experience.

Unfiction and the legacy of transmedia storytelling

One might ask: how did groups like The Cloudmakers communicate so effectively before social media was popular? The answer, as with many online collaborative ventures of this period, lies in forums. In the early 2000s, ARG expert Sean Stacey created the website unfiction.com. This forum space served as a compendium and investigative space for fans of ARGs and similar projects. As the unfiction.com user base grew, it became apparent that some projects – while undoubtedly of interest to the ARG community and similar in both tone and execution – did not fit under the ARG label. Some projects told a story, but without an interactive element; others were restricted to one or two platforms, yet clearly blurred the boundary between fiction and reality. There was no definitive criteria for the kind of art users of the site would discuss, but they all had at least one of the following traits in common: transmedia; Internet-based; interactive, and abiding by the T.I.N.A.G. principle.

The number of names which have been suggested and applied to this artform are countless. Digital Studies professor Zach Whalen notes chaotic fiction, polymorphic fiction and xmedia amongst hundreds of given labels. Whilst ARG remains a dominant term in the community, the name now refers specifically to projects which require player interaction in order for the story to progress (i.e., player actions directly affect the outcome of the game). Whilst Stacey and others felt that ARGs were a definite subgenre of this elusive artform they wished to define, it wasn’t broad enough to encompass all of the projects the community wanted to create and discuss. Thus, Stacey coined the term unfiction: quite literally not-fiction. It is only in recent years that unfiction has picked up traction within its own community, yet compelling arguments have been made for its use. Unfiction analyst Nick Nocturne speaks of the power of unfiction as a label: a term which not only pays homage to the legacy of its creators and players, but also succinctly defines what the genre entails. It is not just fiction: it is unfiction.

As technologies, platforms and storytelling methods continue to innovate, capturing the essence of this fascinating mode of art only becomes more difficult. Yet, there is something prescient about unfiction and transmedia which speaks of the human desire to tell stories. No matter what new mechanics we are granted or how many ways we learn to produce new, interesting narratives, our capacity and need to make art never wavers.

That, I feel, is comforting knowledge to possess.