Browse through any social media platform long enough and you’re bound to come across a multitude of selfies. Typically taken with smartphones, at arm’s length or in mirrors, this seemingly new form of self-expression has come to dominate the digital realm. But look a little closer and you will see that the modern-day ‘selfie’ has a long art historical lineage.

The desire for control over one’s self-image has been a concern of artists for centuries, many of whom have used self-portraiture as a means to represent themselves as they wish to be seen, whilst interrogating notions of identity. Reflecting on the selfie phenomenon, the art critic Jerry Saltz noted, “It’s something like art. They have a certain intensity and they’re starting to record that people are the photographers of modern life.” Though the prevailing medium has changed, the drive to document oneself persists. In this article, we look at the evolution of self-representation and the impulses behind it, from the Middle Ages to the present day.

Albrecht Dürer

In his book The Self-Portrait: A Cultural History, James Hall argues that the genre of self-portraiture began in the middle ages due to the era’s preoccupation with personal salvation and self-scrutiny. The first artist to really master self-portraiture as a form, however, emerged from the cusp between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance period. His name was Albrecht Dürer, a German painter who repeatedly turned to himself as subject matter. His Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight, painted in 1500, depicted himself in the likeness of Christ, with the same coiled hair and fixed, expressive eyes. Physical similarities aside, the symmetrical, head-on composition in which it was painted was almost always reserved for paintings of the messiah, not for artists or regular men. Wearing a fur-lined robe, his clothes mark him out as a man of wealth, style and sophistication. Yet, as a pious man, we can assume this comparison is not to be taken literally — where Christ typically raises his hand, Durer points inward, toward the heart, implying his artistic talent is but a gift from God.

Rembrandt

For other artists, self-portraiture has been a way to document the evolution of the self. With an arsenal of over 80 self-portraits, no one perhaps has been so thorough in this quest as the Dutch master Rembrandt. Through painting, he captured himself in various states throughout his life, documenting his changing fortunes, moods and physical conditions. From an ambitious and self-assured 22 year old, to a worn-out 63 year old grappling with the onset of old age, Rembrandt’s self-portraits demonstrate that the self is never a singular entity, but something constantly in flux, always transforming. As his career progressed, the artist increasingly used self-portraiture as a means of marketing or self-promotion, with many wealthy collectors looking to invest in a portrait of the famous artist. Self-portraiture, to an extent, functioned as advertising which could lead to future commissions, not only visually depicting the artist, but also as a display of technique.

Frida Kahlo

For Frida Kahlo, self-portraiture was a way to process suffering, both physiological and emotional, as well as a means of chronicling her tumultuous relationship with fellow artist Diego Rivera. She intuitively understood the power of the ‘selfie’ as a means of expression, famously stating, “I paint self-portraits because I am the person that I know best. I paint my own reality.” Following a serious bus accident, Kahlo spent many years bedridden, with only herself as a model. As a teenager, her father set-up a mirror above her bed so she could paint herself as she rested. Of the 143 paintings created during her life, 55 of them were self-portraits. One of the most striking examples from her self-reflective oeuvre is The Two Fridas, which encompasses many of her overarching themes: duality, the female experience, and Mexican culture. The painting shows Kahlo doubled, as two near-identical figures sitting next to one another holding hands. Their hearts are exposed, connected by a shared artery, which is cut on one side, and connected to a miniscule portrait of Rivera on the other. This evocative self-portrait, rich with symbolism, depicts a duality of self whilst also expressing the emotional turmoil felt in the aftermath of her divorce.

Cindy Sherman

Equally, self-portraiture has been used by artists to challenge stereotypes. The photographer Cindy Sherman has spent the last 40 years masquerading as a myriad of different characters in order to examine the ways in which we construct and perform identity. These are self-portraits in disguise, created as a means to role play and deconstruct social and sexual stereotypes. Sherman has spent a career transforming herself into wealthy heiresses and killer clowns, imitating film stars and famous paintings alike. Over the last couple of years, however, Sherman has made the switch to Instagram where she has produced a series of cartoonishly caricatured selfies. Unlike her earlier work, whose use of recognizable archetypes suggest a narrative, these new images seem to hold up a mirror to the narcissistic tendencies fuelled by social media. By taking photo-editing technologies to their logical extreme, Sherman’s selfies become grotesque representations of a desire for self-expression gone awry.

What do self-portraiture and selfies have in common?

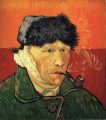

Though there are many distinct compositional differences between traditional self-portraiture and the modern-day selfie, they both share one underlying commonality. Whether used to express emotional depth, such as in the self-portraiture of Van Gogh, or to mythologise the self, as in the silkscreens of Andy Warhol, both selfies and self-portraiture share a desire to capture the essence of one’s life in a particular moment. They reveal a fundamental drive within human nature: the will to record, to document, to preserve. To speak beyond the brush or lens — “I was here”.