Headlines grab us: that is their job. Photojournalism hits home hard: the best examples have become morbid bookmarks in the history of modern man as well as symbols of national identity. This post skims over the surface of visual culture and gives one vague history of culturally, socially and politically engaged artistic practice.

“More confusions, blood transfusions/the news today will be the movies of tomorrow”; Arthur Lee was not wrong when he penned these lines for his band Love bang smack in the middle of the Vietnam War in 1967. Lee, ever the cultural prophet, recognised the cinemagraphic quality that unspooled before him on his television set; others did too. Within twenty years of Love’s Forever Changes LP, The Deerhunter (1978), Apocalypse Now! (1979), Platoon (1986), Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Hamburger Hill (1987) had all graced the big screens the world over. Born on the 4th of July (1989) followed shortly after. Fiona Banner, under ten years thence, compiled all these movies into an 11-hour epic and penned an unreadable compendium of every minute detail entitled The Nam (1997). No movie distinctly begins or ends in this book; they merely exist within their own matrix of cultural signifiers – tanks, helicopters, uniforms, screaming. Blood. Mud. War.

The ongoing ramifications of life-changing, world-impacting occurrences are obviously going to manifest themselves in some visual form but they don’t always have to be edited for pleasure. The immediacy of magnifying a historical moment as it unfolds has been a tactic of artists for hundreds of years – sometimes read as propaganda, sometimes read as fact – the artists behind these works put themselves in the dangerous position of inciting reaction.

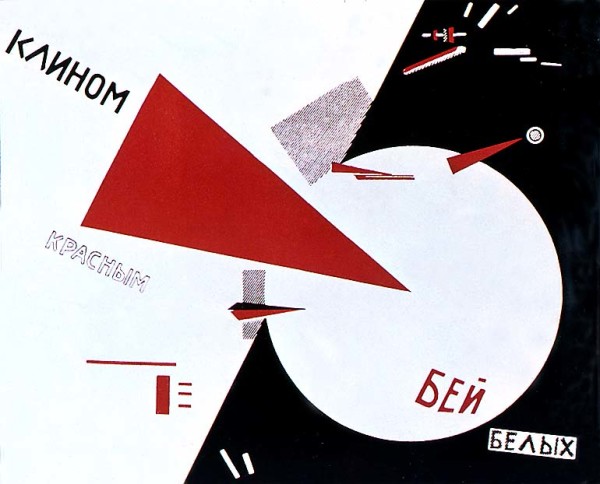

Long before Billy Bragg and Ken Livingston’s moustache, ‘red wedge’ meant only one thing – El Lissitzky. This 1919 poster, ‘Beat The Whites With The Red Wedge’ is an ingenious piece of Russian propaganda. Abstract and direct in the right quantities, the ideals of a freshly revolutionised Russia were easy to grasp, driven and beautiful.

Kenneth Clarke called it “the first great picture which can be called revolutionary in every sense of the word, in style, in subject, and in intention”; Goya’s Third of May 1808 is a testament to the horrors of war. Commissioned by the Spanish government, this painting is stark, chilling and timeless. Many other artists, including Picasso, have found a truth and passion in Goya’s masterpiece, reappropriating the imagery to show that man will always fight man.

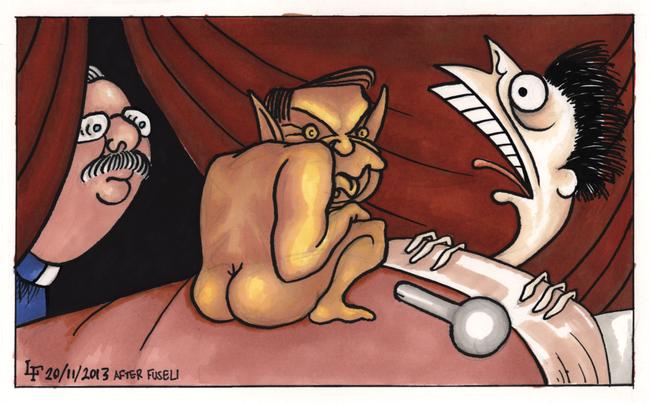

Once images become part of culture and cultural identity, they hold an added weight – political cartoons, as an idea, may be old but they still have the capacity to reflect modern ideas. The great thing about cartoons is that the real message masquerades as pretty, petty and superficial entertainment. Then they bite. And, really, caricatures, cartoons and characters are great at exposing just that – the representation of a real person…

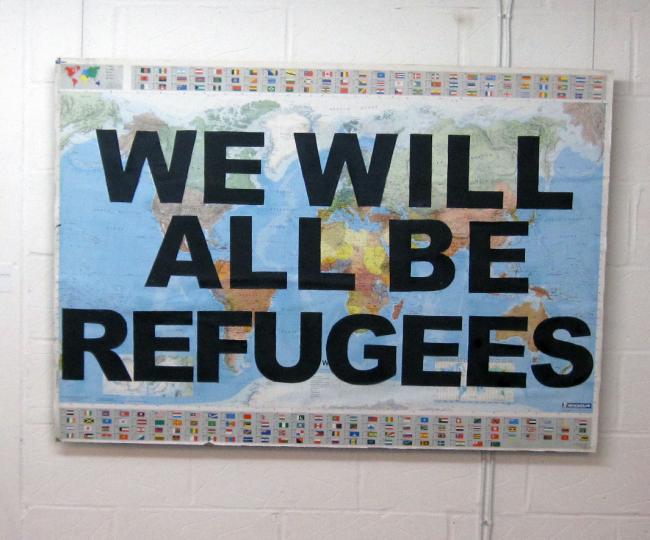

…and then there are those like Celina Teague. Celina’s latest exhibition, I think, therefore I hashtag, which opened last month, was a master work of astute social observation and commentary. The news stories that we skim over, scroll past and flick through deserve some permanence and the glossy Instagram shots that (for some reason) make the headlines need to be contextualised and given a new space to be understood in a new way.

Art exhibitions and beautifully rendered works don’t try and completely, objectively communicate truth, but that is the greatest thing about a socially engaged art practice. Unlike sterile news articles which seem to preach, art humanises stories, makes an attempt to rework exactly what it is that resonates with us and makes a much longer-lasting impression.