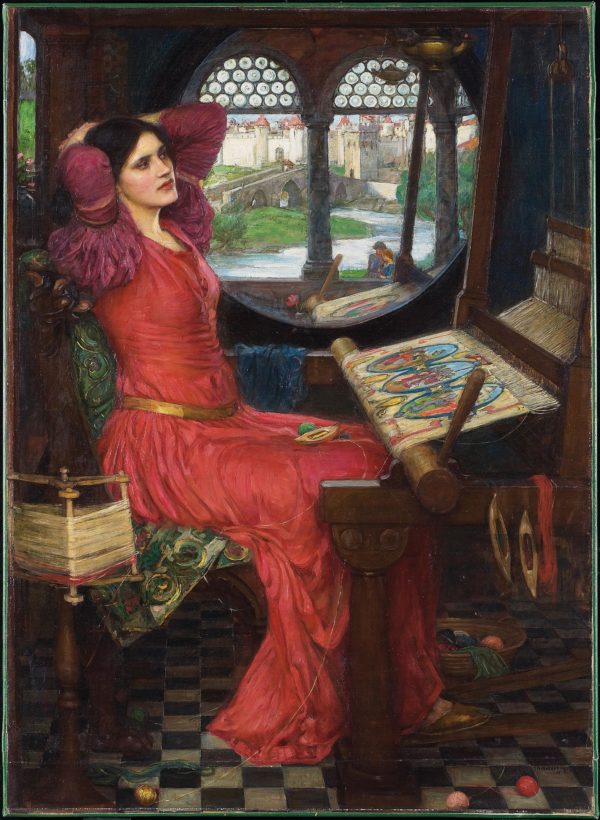

Tapestry is one of the oldest art forms, and has entered deeply into cultural imagination. The root of the word ‘tapestry’ can be traced back to ancient Greece, where the art of weaving also played an important part in mythology, such as in the story of Arachne, turned into a spider by the goddess Athena when she dared to create a superior tapestry. From the height of its popularity in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, tapestry underwent a decline in the 18th century, but today is enjoying a rebirth, fuelled by contemporary artists embracing its ancient techniques.

Tapestry is a form of weaving produced on a loom using ‘warp’ and ‘weft’ threads.

Warp threads are strung between a loom’s two rollers, and are the ‘beams’ of a tapestry, providing it with strength and structure, but becoming hidden during the weaving process. The more warp threads a tapestry has, the more intricate and detailed it can become, and the longer it takes to produce.

What is tapestry?

The weft is the yarn that is threaded through the warp to build patterns. Weft threads do not run continuously across the tapestry; instead different threads are used in segments to create small blocks of colour, which combine to create the overall design.

In Europe, tapestries have traditionally been made using wool for both the warp and weft. Silk was occasionally employed to add fine detail in the weft, with metal threads reserved for only the most precious works.

The ‘golden age’ of tapestries

From the Middle Ages to the Baroque, tapestries were far more expensive than paintings, and many frescoes tried to mimic the style of their more expensive woven counterparts. (Raphael’s tapestries for the Sistine Chapel, for example, cost five times as much as Michelangelo’s ceiling to produce, due to the gold thread and labour required to create them.) Tapestries appealed to an aristocratic audience as both decorative and functional objects that could be used to insulate rooms, and could also be rolled and moved easily between palaces.

The iconography of tapestries reflect the intellectual and cultural history of their age: in the late Middle Ages, works such as The Lady and the Unicorn series explored Neo-Platonist ideas about the senses, while others reflected contemporary aristocratic life in depictions of pastimes such as hunting.

Tapestries were produced in workshops by weavers, following designs called cartoons. These would be painted at full scale on cloth or paper, and either attached to the loom or hung behind it, guiding the weavers as they worked. By the time of the Renaissance and Baroque, however, patrons were commissioning tapestry designs by leading painters such as Raphael and Rubens, whose primary medium was not tapestry, creating a challenge for workshops to interpret and execute their designs.

The decline — and revival — of tapestry

Art historians have traditionally charted a decline in the originality and quality of tapestries from the mid-17th century onwards, and the art form experienced a serious collapse after the 18th century, as workshops experienced increasing pressure to produce works more quickly.

In the 19th century, the designer William Morris (1834–1896) advocated for a return to craftsmanship of the pre-industrial age, and sought to revive the art of tapestry. In his workshops at Merton Abbey, Morris oversaw the production of the most celebrated tapestry series of his age: six tapestries depicting the quest for the Holy Grail, which were woven between 1891 and 1894.

A revived interest in the medium continued into the 20th century, when the paintings of artists such as Picasso and Matisse were reproduced in tapestry. A true renaissance in tapestry as a creative medium, rather than simply a reproduction of other media, however, was instigated in the 1930s by the French painter and designer Jean Lurçat (1892–1966). After years of experimentation, Lurçat worked with François Tabard, master weaver at the Aubusson manufactury, to formulate a code of principles that would transform tapestry into a true collaboration between weaver and designer, and an art form in its own right, and in the second half of the 20th century tapestry attracted artists such as Jean Arp (1887–1966), Victor Vasarely (1906–1997), and Alighiero Boetti (1940–1994).

Tapestry today

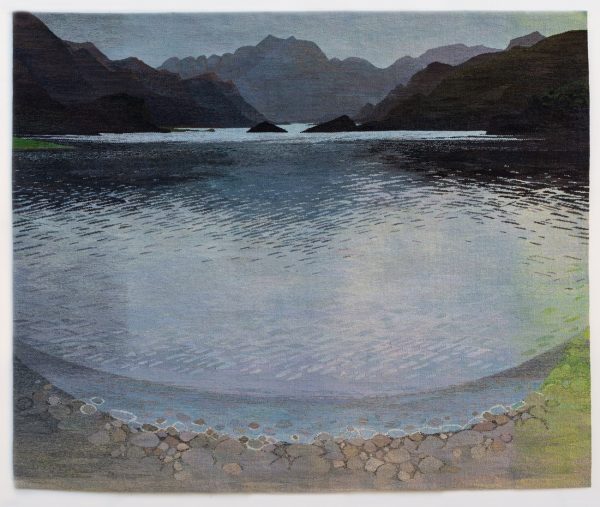

Today, many artists continue to be drawn to tapestry’s expressive quality, versatility, and suitability for both abstract and figurative designs.

One contemporary artist who has embraced the possibilities of tapestry is Joan Baxter, whose award-winning tapestries depict and explore the landscape and heritage of the far north of Scotland. For Baxter, tapestry has only come into its own as a medium in recent years, and is now truly speaking in its native language. “My work is designed to be subtle, thoughtful and subliminal”, she explains. “At the outset I have no clear picture of how a finished tapestry will look as the piece develops and changes during the weaving. I find the measured pace and technical constraints of weaving curiously liberating and only when I am weaving do the really good ideas come to me, so my work could never exist in any other medium.”

Where to learn more

The British Tapestry Group lists a directory of members throughout the UK offering short courses in tapestry weaving.

For those truly bitten by the tapestry bug, The West Dean College of Art and Conservation offers foundation and graduate diplomas in tapestry weaving, and MFAs.