Ink isn’t merely a highly versatile and responsive art material — it also holds a position of fundamental importance in our recorded history, and the recording of history. How would we have documented so much of our past, if it wasn’t for ink?

Furthermore, as a drawing and painting medium, ink has been available to us for as long as almost any alternative. The history of ink can be traced back to about 2500 BC in China and Egypt, and it seems that it didn’t take too long after that for it to take flight as an art material.

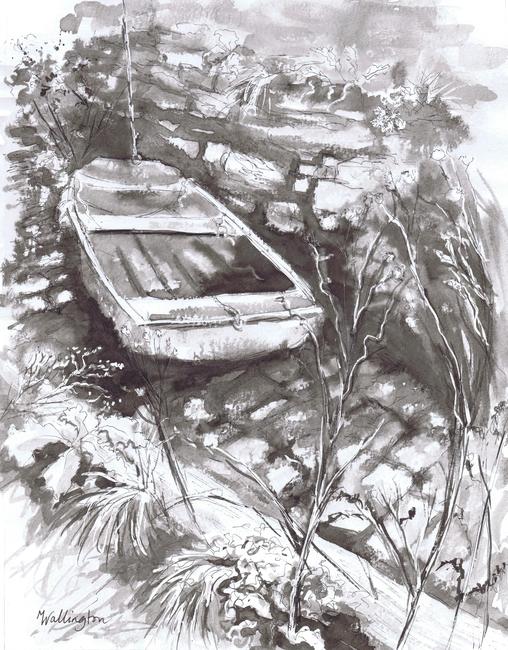

Nor should that shock us; ink is easy to use, free-flowing and quick-drying. It has a permanence that few other artistic mediums can match, but also its own rich character. All the while, it is highly responsive to an artist’s unique personality and manner of working.

The scope for the imaginative artistic use of ink has therefore scarcely dimmed through the centuries, as every artist has shown new possibilities for its use. Here are a few examples.

Isn’t ink just about line?

Well, if it is, it certainly doesn’t have to be! In fact, the notion that you can only really use ink for pure line is largely Western, and may stem from printing and reproduction requirements.

Diluting ink with water is one of the first, simple steps that you can take to start discovering the rich washes one can create from ink, generating tonal variations ranging from the densest black to the palest and most delicate grey.

But you can also be as limited or as expressive with colour as you like

If you are only just venturing into the world of ink as an artist, you shouldn’t necessarily feel too pressured to start adding splashes of colour.

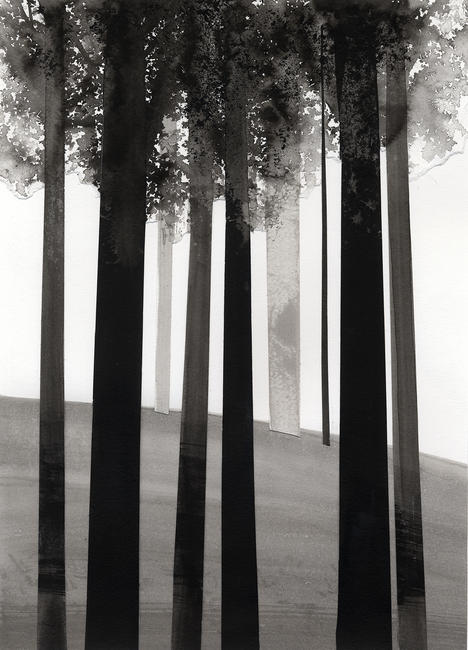

Traditional Oriental ink painting, for example, has long valued monochrome for expressing a subject’s true form and inner spiritual qualities. Although colour is frequently added to such paintings, it is considered an embellishment, with the painting’s fundamental meaning or essence instead depending on the artist’s use of pure black.

Such an attitude is beautifully summed up by the ancient Chinese maxim, “When you have ink, you have colour.” For much more recent historical examples of how this tenet has retained its relevance, you might look to such abstract expressionists as Robert Motherwell (1915-1991) and Franz Kline (1910-1962), whose works were often especially powerful when they restricted themselves to a monochrome approach.

The Pennell vs Renoir problem

Another great historical case study for how artists have negotiated the creative dilemmas presented by ink is the critical connection between two 19th-century contemporaries, Joseph Pennell (1857-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919).

No one can question that the American artist and author, Pennell, was dedicated to the technical aspect of his craft, as is demonstrated by his intricate etchings and pen and ink drawings of architectural subjects. He was a master of delicate pen work.

However, his concerns for technical perfection were also apparent in his sometimes acidic comments about his fellow artists as a writer. He described Renoir’s own pen and ink drawings, for instance, as having “absolutely uninteresting and clumsy line”.

In fairness to Pennell, it is hardly Renoir’s use of a pen for which the leading Impressionist painter is most renowned in the popular imagination today. But when the 21st-century viewer actually consults such pen-and-ink creations by the latter as Bather Drying Herself, a debate could be had as to which artist’s works in the medium have aged best.

Renoir may have been tentative in his use of a pen, but his ink works also show the sound drawing and good design that characterise a master. By contrast, as surmised by author Fritz Henning, the craftsmanship of Pennell’s drawings “cannot be faulted. But as art, his pictures seem sterile and overwhelmingly factual. How much more exciting might they have been if there were a bit less emphasis on perfect strokes and a little more spontaneous emotion of [Antonio] Casanova [y Estorach] or [Francisco de] Goya.”

But of course, both the Pennell and Renoir schools of thought on ink work have their validity — so we’ll leave it up to you to consider which category you may fall into as an artist.

Don’t be afraid to take a dive into the in-depth world of ink

From the days of Antonio Pisanello (c. 1395-1455) and Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) to the likes of Anders Zorn (1860-1920) and Emil Nolde (1867-1956), and encompassing the simplest pen and brush work, relief printing and lithography alike, artists down the generations have continued to show the creative inexhaustibility of ink.

What kind of template, then, could it serve as for your own art practice in 2019? Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments section below.